The Hay Wain, 1821 by John Constable

Canvas Print - 2900-COJ

Location: National Gallery, London, UKOriginal Size: 130.2 x 185.4 cm

Giclée Canvas Print | $57.74 USD

Your Selection

Customize Your Print

By using the red up or down arrows, you have the option to proportionally increase or decrease the printed area in inches as per your preference.

*Max printing size: 41.1 x 59.1 in

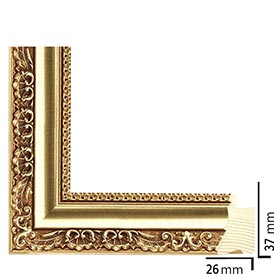

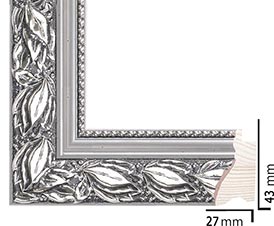

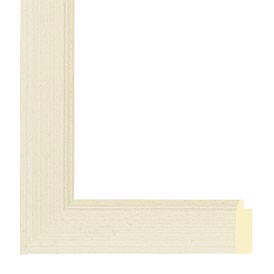

*Max framing size: Long side up to 28"

"The Hay Wain" will be custom-printed for your order using the latest giclée printing technology. This technique ensures that the Canvas Print captures an exceptional level of detail, showcasing vibrant and vivid colors with remarkable clarity.

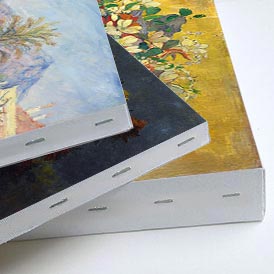

Our use of the finest quality, fine-textured canvas lends art reproductions a painting-like appearance. Combined with a satin-gloss coating, it delivers exceptional print outcomes, showcasing vivid colors, intricate details, deep blacks, and impeccable contrasts. The canvas structure is also highly compatible with canvas stretching frames, further enhancing its versatility.

To ensure proper stretching of the artwork on the stretcher-bar, we add additional blank borders around the printed area on all sides.

Our printing process utilizes cutting-edge technology and employs the Giclée printmaking method, ensuring exceptional quality. The colors undergo independent verification, guaranteeing a lifespan of over 100 years.

Please note that there are postal restrictions limiting the size of framed prints to a maximum of 28 inches along the longest side of the painting. If you desire a larger art print, we recommend utilizing the services of your local framing studio.

*It is important to mention that the framing option is unavailable for certain paintings, such as those with oval or round shapes.

If you select a frameless art print of "The Hay Wain" by Constable, it will be prepared for shipment within 48 hours. However, if you prefer a framed artwork, the printing and framing process will typically require approximately 7-8 days before it is ready to be shipped.

We provide complimentary delivery for up to two unframed (rolled-up) art prints in a single order. Our standard delivery is free and typically takes 10-14 working days to arrive.

For faster shipping, we also offer express DHL shipping, which usually takes 2-4 working days. The cost of express shipping is determined by the weight and volume of the shipment, as well as the delivery destination.

Once you have added the paintings to your shopping cart, you can use the "Shipping estimates" tool to obtain information about available transport services and their respective prices.

All unframed art prints are delivered rolled up in secure postal tubes, ensuring their protection during transportation. Framed art prints, on the other hand, are shipped in cardboard packaging with additional corner protectors for added safety.

Painting Information

In 1821, the painting now commonly referred to as The Hay Wain made its appearance at the Royal Academy. At the time, Britain’s countryside was gradually receding in the face of accelerating industrial forces - factories, locomotive engines, and steam power dominated the output of many contemporary artists. Yet here, there is no intrusion of modernity. Instead, the canvas offers a vision of unaltered rural Suffolk. The place portrayed is close to Flatford Mill, a watermill leased by the artist’s family. A closer look reveals the edge of the mill’s red brick wall at the painting’s extreme right, with Willy Lott’s modest farmhouse on the left. The wagon at the center fords a shallow millpond and is poised to cross over to the fields on the far side where the rhythm of the harvest continues, signaled by the men at work with scythes and pitchforks. When it was first unveiled under a different title, “Landscape: Noon,” it found a degree of critical admiration, but no purchase.

Essential to understanding this artwork is its arrangement of elements. The house on the left and the small boat on the right give the composition a sturdy foundation, flanking the central activity: a team of horses pulling the wooden wagon through the reflective waters. The eye is drawn across the scene in stages - from the foreground, where a dog stands on muddy ground, to the middle where the horses are halted halfway through the ford, then off to the distant meadows. Trees anchor the center and stretch upward, crowned by shifting skies. These clouds hold as much drama as the rural labor below, their shapes suggesting passing weather. In keeping with earlier Flemish and Dutch traditions, the painting emphasizes nature’s lived reality rather than any classical notion of a perfect Arcadia.

Yet this is not simply documentation. The palette, dominated by earthy greens and browns, reveals how the artist sought to portray the world with carefully attuned nuance. The scene is neither bright nor somber. Instead, it captures an atmosphere that hovers between sunshine and a possible shower, reflecting England’s mercurial weather. One notes the flashes of deeper red scattered throughout - the bricks of the farmhouse, the horses’ fringed collars, and the rooflines. These glimpses of color lend warmth and subtle contrast, balancing the more subdued tones. Overall, the colors register the dampness of the fields, the moisture in the summer sky, and the sense of soft, enveloping light that pervades the landscape.

The approach to technique shows an unrelenting fascination with nature. While the painting was executed largely in London, it was grounded in numerous plein-air sketches made in the Stour Valley. In the finished canvas, the brushstrokes remain visible and energetic, especially in the foliage and sky. One can sense the underpaint layers where a brown ground was sometimes left exposed, lending an immediacy to certain passages. Working from smaller oil studies - one featuring the hay wagon itself and others focusing on Willy Lott’s farmhouse - the artist built a large-scale composition that retains a spontaneous character. The paint application in the sky, for instance, shifts from thinner layers to denser deposits, articulating clouds that appear to shift and break with the breeze.

Historically, this painting sits among a series of large works the artist produced featuring the River Stour, all shown at the Royal Academy between 1819 and 1825. Though overshadowed by more dramatic and urban subjects of the day, this depiction of an older, slower-paced life may have struck some as anachronistic. Yet it eventually gained acclaim beyond British shores. At the 1824 Paris Salon, it garnered significant attention, winning a gold medal from Charles X. Stories circulated of French visitors to the earlier Royal Academy exhibition who were impressed by the unadorned realism and raw truth of the English rural setting. In retrospect, it stands as a reminder of how an artist’s devotion to everyday scenes could become radical when confronting a Europe where modern forces were inexorably on the rise.

Viewed in this light, the painting demonstrates a desire to remember and immortalize the rural Suffolk of its creator’s childhood. The wagon, which might not precisely match the design of period hay carts, is in fact reminiscent of earlier Flemish paintings, echoing the depth and breadth of Rubens’s landscapes. Its presence in the water - front wheel already turning - draws the viewer into a narrative of ongoing labor, balanced by the stillness of a scene largely devoid of mechanized invention. These details underscore how the artwork transcends simple description. It distills a lived environment, shaped by old, long-standing rhythms of harvest and river crossing. The enduring appeal of this canvas lies in its ability to communicate the essential experience of an unhurried countryside, observed with careful scrutiny and affection, yet presented with the sweeping ambition of a grand history painting.

Even the name by which it is now known was never the artist’s choice - it was a nickname given by a close friend, emphasizing the central motif. This quiet composition, celebrating the harmony of land, water, and humble labor, is at heart an invitation. Observers can linger over the dog in the foreground or note the figure stooping by the water with a pitcher, adding small ripples of humanity. For all its gentle qualities, the painting quietly asserts a conviction: that the everyday scenery of East Anglian life holds as much aesthetic power as any classical ruin or grand industrial feat. In capturing the essence of this corner of England, it captures also the pulse of rural existence - seemingly timeless, though in 1821 already threatened by the approaching currents of modern progress.